Les Poilus d’Alaska

Alaskan husky at Riley Creek Campground, Denali National Park and Preserve, Alaska, USA. Image credit: Denali National Park and Preserve, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Man’s best friend has assisted people in Earth’s northern regions for centuries to travel and hunt for food, serving as sled dogs in Scandinavia, Siberia, Alaska, modern-day Canada, and Greenland. Analyses of several dog breeds such as the Siberian Husky (Chukotka), Samoyed, and Canadian Eskimo Dog, show their lineage from members of the wolf family. Variances resulted from migration and cultural and sociological differences that prioritized or minimized specific traits depending on the humans who raised, bred, and worked with the animals. Farther to the south in France, the story of how the Alaskan Husky came to be the most prevalent breed of sled dog in the country is a much more recent one.

By the thick of winter in 1914, the Great War had broken out and Germany had made significant inroads into French territory. In the Vosges mountains of eastern France near the German border, heavy snowfall and bitter cold virtually cut off supply lines and stranded wounded soldiers in need of medical attention when vehicles, horses, and mules were unable to reach military units and villagers. Although a trickle of replenishment goods arrived via soldiers on foot with only what they were able to carry, the shortages contributed to substantial suffering and loss of life. As French leaders worried about how to confront another winter once it became apparent that hostilities would not be soon resolved, Captain Louis Moufflet and Lieutenant René Haas submitted a proposal to bring Alaskan sled dogs to France. Both men had worked in Alaska and witnessed the hardiness and utility of Alaskan Husky dogs prior to the war. In the face of initial resistance, they were gradually able to convince their superiors to support their initiative in preparation for the winter of 1915. That summer, the pair was authorized to join forces with musher Scotty Allan to train and transport several hundred dogs from Nome, Alaska to France. Operation Poilus d’Alaska was underway.

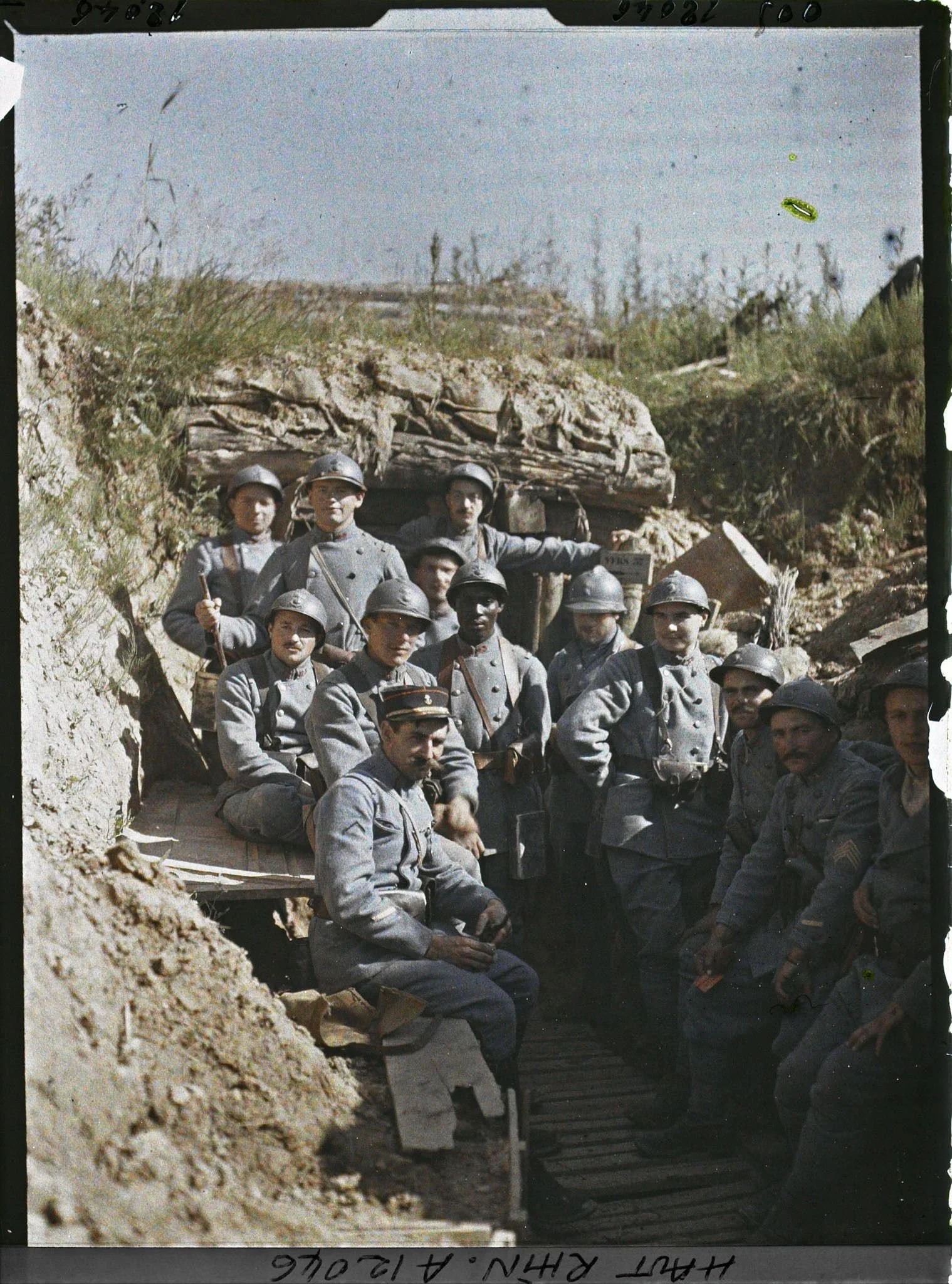

Group of ‘poilus’, Bois d'Hirtzbach, Haut-Rhin, France (June 1917). Image credit: Paul Castelnau, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Les Poilus was a nickname referring to soldiers in the French infantry. Translated as ‘hairy ones’, the term reflects the facial hair of many French infantrymen while carrying the connotation of bravery and fortitude, characteristics that were typical of the rural Frenchmen that often served in the trenches in the Great War. Although most involved in the operation had never seen a sled dog before, the descriptions of them provided by Moufflet and Haas fit the reputation of poilus. The animals were certainly covered in fur and would be assigned to missions requiring bravery and fortitude. However, their procurement and deployment needed to take place in utmost secrecy.

Allan was a renowned musher as a three-time winner of the All-Alaska Sweepstakes race from Nome to Candle, Alaska. His successes in sled dog racing served as the inspiration for Jack London’s protagonist in The Call of the Wild. Allan began to discreetly scour Alaskan territory for suitable dogs, amassing equipment and provisions along the way under the guise of building his own racing operation. Haas joined him in August while Moufflet worked from New York to raise funds and cajole American companies into providing protection for the return journey across the Atlantic. Moufflet continued on to Canada and succeeded in procuring more than 300 dogs by traversing Quebec on horseback and by canoe. Allan, Haas, and another hundred-odd sled dogs joined them in late October after traveling under military guard across Canada. The unusual cargo and press coverage drew unwanted attention, and the men’s challenges grew as German spies repeatedly attempted to poison the dogs and assassinate the project leaders.

Musher on the Petit Mont-Cenis Plateau during la Grande Odyssée 2007. Image credit: Choumert, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

With winter quickly approaching, the group turned to the task of moving dogs and equipment to France despite the understandable reticence of ship captains to navigate through waters that concealed German U-boats, particularly with barking dogs that could reveal their position. A large sum of money finally convinced a steamboat captain to undertake the journey provided that the dogs remained in the hold where their barking would be muffled, which Allan refused to do to ensure the dogs’ health. He offered to spend a night with the dogs and the captain so the latter could witness Allan’s ability to keep his charges calm and quiet. And thus, only days before the St. Lawrence River froze solidly enough to impede maritime passage, the Pomeranian steamed toward the Atlantic Ocean on its two-week crossing to Europe.

Moufflet met the ship, Allan, Haas, and their precious cargo at Le Havre with a handpicked group of chasseurs alpins, mountaineering members of the French Army. After careful training from Scotty Allan, the newly formed sections d’équipage canins d’Alaska (SECA) proceeded to the front lines of the Vosges. As Moufflet and Haas had anticipated, the Alaskan Huskies were capable and trustworthy in all sorts of wintry weather, quietly delivering supplies, rescuing wounded troops, and enabling access to remote spots instrumental to the defense of France. Many of the dogs fell under enemy fire, several were honored with the Croix de guerre medal, and some were adopted after the war by their handlers and local residents. Today, their descendants provide tourists with sled dog excursions across France and are trained to race in events such as La Grande Odyssée in the French Alps.

In 2015, a memorial commemorating the 100th anniversary of the arrival of the sled dogs was dedicated to the Poilus d’Alaska that had played an instrumental role in the Great War. It was jointly erected by the Souvenir Français, the Nanook de Bischwiller sled dog club, and the Musée Serret, a museum focused on local history and how it shaped the region. Although the Poilus d’Alaska were the only time that France employed sled dogs during wartime, the operation was kept secret long after the armistice was signed. The amazing story of these humans and dogs can now be seen in Sled Dog Soldiers, a film directed by Marc Jampolsky available on Amazon Prime and Apple TV.

Jeu de français

Members of the Poilus d’Alaska were not the only animals to be honored as military heroes during the Great War. A homing pigeon called Cher Ami was awarded the Croix de guerre medal for delivering essential messages during the Battle of Verdun. Millions of other animals served during wartime, including horses, mules, camels, elephants, dogs, cats, and even slugs, which were able to survive repeated exposure to mustard gas and were carried by soldiers as a warning system of gas attacks.

Use the English language animal names in the crossword below to fill in the squares with their French equivalents.

Subscribe to our newsletter to receive Art de vivre posts, information about courses, Conversation Café, special events, and other news from l’Institut français d’Oak Park.