Liberty Leading the People

The French Revolution that began in 1789 is the most well-known but not the last of public uprisings as French governance bumpily transformed from a monarchy to the current Fifth Republic. Following the July Revolution of 1830 known as Les Trois Glorieuses, the French Romantic painter Eugène Delacroix cemented his place in history with La Liberté guidant le peuple (Lady Liberty leading the people), a painting that includes a personification of French republicanism in the form of a female figure known as Marianne.

Eugène Delacroix, Liberty Leading the People, 1830. Louvre Museum, Paris, France. Image credit: Eugène Delacroix, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

King Charles X succeeded his brother Louis XVIII as the leader of France in September 1824. Within months, he and his ministers introduced several proposals that were viewed by many as a failure to respect certain principles of the Charter of 1814, a constitution that had been adopted as a condition to the Bourbon Restoration. By the spring of 1830, the Chamber of Deputies passed a vote of no confidence in the king and his administration, who retaliated by calling for the dissolution of Parliament and delaying new elections for several months. When the liberal opposition won nearly two-thirds of legislative seats in July elections, Charles X and his ministers imposed the July Ordinances in an attempt to alter the Charter of 1814 by decree, believing that it was the king’s responsibility to quash growing unrest by restoring order as he saw fit. These ordinances annulled the election results, suspended freedom of the press, and redefined voting rights as well as reorganizing the elected governing bodies and their powers.

The publication of the July Ordinances in the official government newspaper on Monday, July 26 failed to achieve the order that the king intended. Merchants and business owners who learned that they would no longer be eligible to run for legislative office reacted by closing their businesses, leaving their employees idle. Newspapers that were deemed unsympathetic to the king were censored, but some of their employees banded together to compose a joint protest document. Discontent grew across numerous swaths of society and crowds began to gather as military troops were deployed around Paris on Tuesday. As night fell, Parisians expressed their anger and frustration by shouting and hurling random items at the soldiers, who countered with armed force. The next day, rioting continued while a group of opposition leaders drafted a petition to withdraw the ordinances. Charles X and his advisers, holed up in nearby St. Cloud, stood fast in their decisions as well as maintaining their physical distance from the French citizens, hoping the latter’s ammunition and fervor would drain away quickly.

Eugène Delacroix, Self-portrait with Green Vest (1837), Louvre Museum, Paris, France. Image credit: Eugène Delacroix, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

By Thursday, Paris was dotted with improvised barricades and government buildings had been infiltrated with the blue, white, and red of the French flag raised high above them as a symbol of democracy. More than a few of the king’s soldiers defied orders and deserted their posts. These three ‘glorious days’ forced Charles X to abdicate and flee from France. Opposition politicians convened and named Louis Philippe I of the House of Orléans to succeed him as a constitutional monarch.

Delacroix was already a successful artist by 1830, having exhibited his canvases The Barque of Dante at the 1822 Paris Salon, The Massacre at Chios there two years later, and The Death of Sardanapalus at the 1828 Paris Salon. In a letter to his brother in October 1830, Delacroix noted that “. . . if I haven't fought for my country at least I'll paint for her.” La Liberté guidant le peuple (Lady Liberty leading the people) was accepted for exhibition at the 1831 Paris Salon. A leading figure in the French Romantic art movement, Delacroix used vibrant colors and worked expressively to convey action and emotion in contrast to the ordered composition of the then-prevailing Neoclassical style. His choice of subject matter often aligned with his repudiation of strict classical principles by depicting current events as social commentary rather than conveying moral lessons from mythology and ancient history. Delacroix believed that art provided a ‘mysterious bridge’ that could connect its viewers with the spirit of the figures within the art itself.

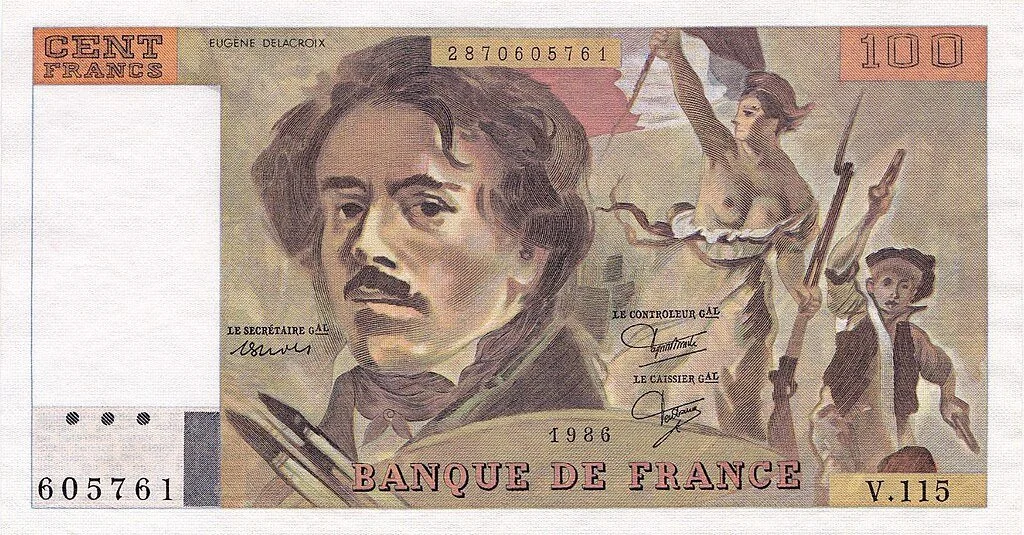

French 100-franc bill, 1986. Image credit: French Banknote Designers (No copyright), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

La Liberté guidant le peuple, while inspired by the events Delacroix witnessed in July 1830, is often presumed to portray the 1789 revolution since its elements are representative of the country’s repeated struggles toward republicanism. Liberty in the form of a woman wearing a red Phrygian cap reigns at the center of the painting. Since the Roman era, freed slaves were given a similar cap called a pileus which signified liberty. Red Phrygian caps appeared along with blue, white, and red cockades among the revolutionaries of 1789 and subsequent years. The illumination of Liberty holding the French tricolor flag high draws attention to the triumph of freedom over the struggle below. Surrounding the woman are figures that represent different strata of French society united in their pursuit of freedom, as well as others who have perished in the fight. The Cathedral of Notre-Dame is apparent in the background separated by fog and smoke from the freedom seekers.

The French government purchased Delacroix’s painting in 1831 to hang in the Palais de Luxembourg but it was soon removed for its overt revolutionary message. Only after the Third Republic was installed did La Liberté guidant le peuple return to public display, joining the collection of the Museé du Louvre in Paris in 1874. Both Delacroix and a portion of his iconic work were chosen for the front side of the French 100-franc bill from 1979 through 1999, when the French currency was replaced by the euro. Meanwhile, images of Marianne as a symbol of liberty and the French Republic have continued to grace French coinage, including euros, and official government documents as a reminder of the power of the people and the times during history that they took action to assure it.

Jeu de français

France experienced several revolutions and conflicts to defend its constitution, citizens, and sovereignty over the centuries. Several of the symbols that endure date from the French Revolution of 1789-1799. Try your hand at the quiz below, which includes some of the references from above.

Subscribe to our newsletter to receive Art de vivre posts, information about courses, Conversation Café, special events, and other news from l’Institut français d’Oak Park.