Millet, the Peasants’ Artist

Painter Jean-François Millet, 1856-1858. Image credit: Gaspard-Félix Tournachon known as Nadar, restored by Adam Cuerden, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Born into a farming family in Normandy in 1814 just as Napoleon’s reign was crumbling and the Bourbon Restoration about to materialize, Jean-François Millet did not seem destined for a revolutionary existence. However, his agrarian upbringing, elements of classical education taught to him by local clergy, and his clear aptitude for the visual arts coincided with political movements of 19th century France to position Millet as a revolutionary of sorts with his choices of subject matter and style in his paintings. Millet’s work Des Glaneuses (The Gleaners) was met with a disdainful and largely negative reception at the 1857 Paris Salon. However, this masterpiece of social commentary and Millet’s other artwork substantially influenced numerous artists who upended French and European painting while the posthumous surge in the market value of Millet’s art prompted significant changes in resale rights for artists and their heirs.

Jean-François Millet spent his first two decades in northwestern France near the coast of the English Channel. These formative years were shaped by working on the farm and in the fields, attending the local school and receiving informal education from the village priests and his elders, and being surrounded by family members who lived their faith and pointed out the wonders of nature and its beauty to him. Millet’s father, Jean-Louis-Nicolas, sent him fifteen kilometers east to study art in Cherbourg in 1833, where his teachers helped make arrangements for Millet to move to Paris to attend the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in 1837. A mismatch for the prevailing academic style espoused by the school and the formalities of Parisian society, Millet lost his scholarship and left the École des Beaux-Arts in 1839 after the rejection of his first submission to the Paris Salon.

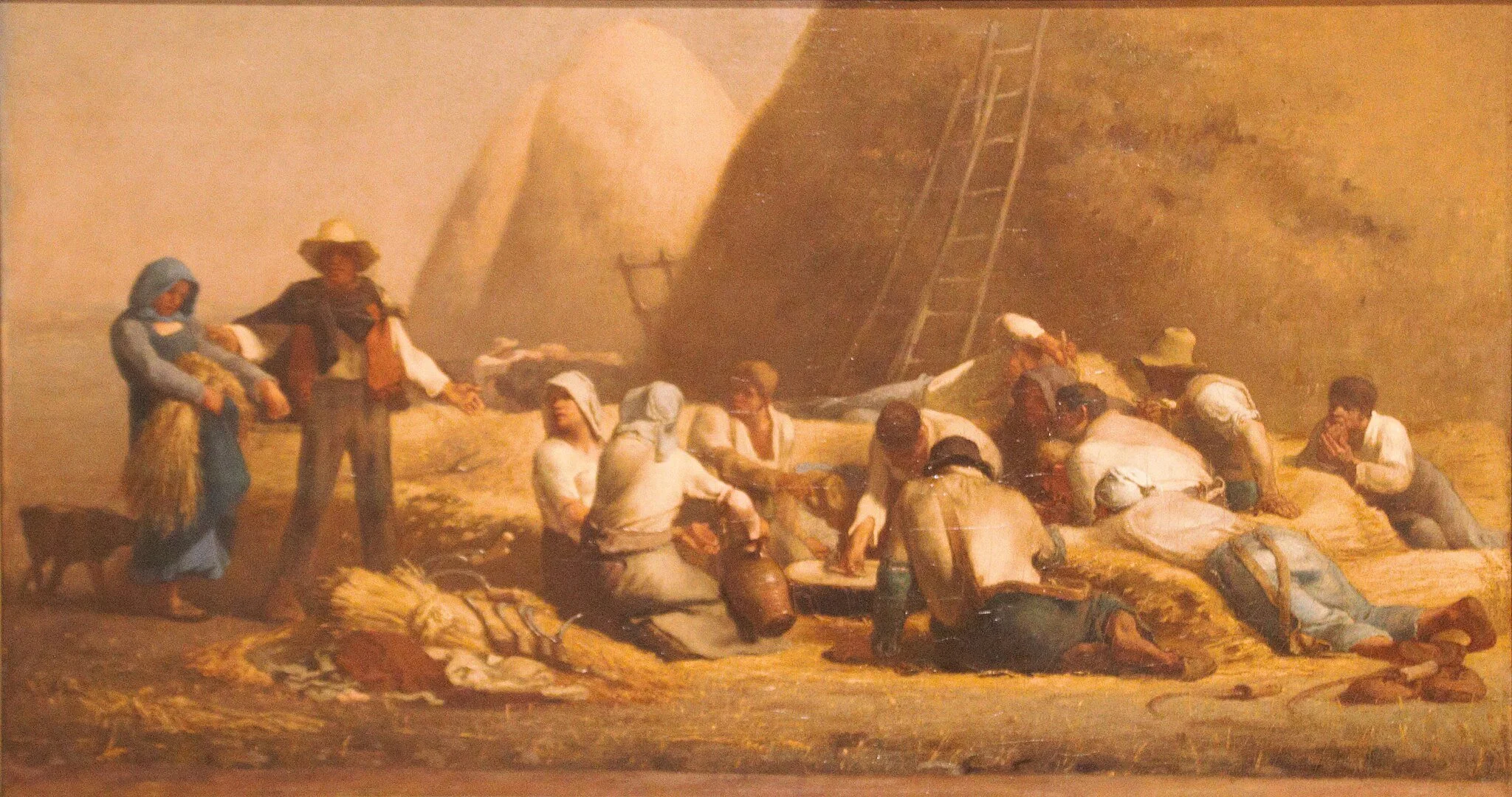

Le repos des Moissonneurs / Harvesters Resting (Ruth and Boaz) (1850–1853), Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Massachusetts. Image credit: Jean-François Millet, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

A portrait painted by Millet was accepted for the 1840 Salon so he began a career as a portraitist, shuttling between Paris and Cherbourg for several years. While in Paris, Millet expanded his network of artists and colleagues and experimented with different styles and topics while trying to develop his own vision. During the 1840s, he achieved varying levels of artistic success but despaired of being capable of supporting his growing family via his painting career. The February Revolution of 1848 and a cholera epidemic pushed Millet to move to Barbizon sixty kilometers southeast of Paris where numerous artists had settled and visited since the late 1820s. This literal change of scenery apparently rekindled the artist’s childhood influences and inspired Millet to paint what he knew best – people of the land and teachings from his religious upbringing. He also moved away from idealized scenes of Neoclassical art and the drama of Romantic painting to a Realist style more in line with his subjects. A government official, Alfred Sensier, became Millet’s patron of sorts by footing the bill for his art supplies in exchange for some of his finished work while allowing the painter to also sell to others. Millet also took on students, including William Morris Hunt, a member of a prominent New England family.

Millet spent the next few years developing his own style, resulting in the success of Le repos des moissonneurs/ Harvesters Resting (Ruth and Boaz), a medal winner at the 1853 Paris Salon. Originally inspired by the Bible story of Ruth and Boaz, Millet produced numerous studies before changing the title and focus of the painting from the couple’s story to the workers taking their midday rest from hard work. He held a lifelong belief in the dignity and Godliness of labor, having much firsthand experience from his farming days, and gave credit to the products of the workers’ efforts in the form of large haystacks in the background. Despite the award, some art critics negatively perceived the painting as displacing Biblical figures in favor of unworthy lower-class individuals.

Des Glaneuses / The Gleaners (1857). Oil on canvas, 83.5 x 110 cm (32.8 x 43.3 in). Musée d'Orsay, Paris. Image credit: Jean-François Millet, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The artist stayed true to his agrarian roots and continued to paint what he knew and respected. He combined his classical training in art technique with a realistic approach to scenes and people he saw around him in the country, making reference to religious themes in his artwork rather than placing them at the forefront. Des Glaneuses (The Gleaners), a large (nearly 3x4 feet) depiction of three women gleaning against the backdrop of an abundant harvest, was accepted for exhibition at the 1857 Salon. Much of the Parisian art world perceived the painting as an undue glorification of laborers and a socialist threat to the prosperous classes. Less than a generation removed from the February Revolution and the July Revolution of 1830 that preceded it, France had been fitfully evolving from monarchy to empire to republic and around again for decades. Facing the reality of the country’s lower classes was deemed highly inappropriate, particularly as the principal focus of a sizeable canvas, but it was also frightening. The poor reception of Des Glaneuses was reflected in the dearth of purchase offers for the work, which Millet reluctantly sold for less than asking price.

During the 1860s, Sensier was joined by others in supporting Millet with commissions that allowed him to work steadily and burnish his artistic reputation. Morris Hunt and fellow Americans purchased several of Millet’s paintings and displayed them in the United States. The 1867 Paris Exposition included an exhibition of Millet’s canvases and the next year he was honored as a Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur. By 1870, he was invited to serve on the jury of the Salon. But the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War temporarily displaced the Millet family from Barbizon and the painter’s health began to deteriorate. Jean-François Millet passed away in 1875.

He left behind much more than a lifetime of artwork. Millet has been cited by numerous artists as a key influence, including Vincent van Gogh, Claude Monet, Georges Seurat, and Salvador Dalí, as well as photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson, poet Edwin Markham, and filmmaker Agnès Varda. After Millet’s death, a steep rise in the sales price of his paintings contributed to the establishment of Artists’ Resale Rights, known as droit de suite, in France and then across Europe. When his work L’Angélus (The Angelus, 1857-1859) was sold not long after Millet’s death for over half a million francs, the contrast with the 1,000 francs that Millet had received from its initial sale was noted as grossly unfair. This discrepancy was highlighted in the push to legally require a share of downstream profits to return to the artist and his/her estate and heirs, which was codified into French law in 1920.

Jeu de français

Millet is quoted as commenting that “To tell the truth, the peasant subjects suit my temperament best; for I must confess, even if you think me a socialist, that the human side of art is what touches me most.” His affinity for the land and those who worked it is shared by all who benefit from the bounty of harvests in the current season.

Call on or expand your French fall vocabulary by finding 24 French words pertaining to l’automne in the word search below.

Subscribe to our newsletter to receive Art de vivre posts, information about courses, Conversation Café, special events, and other news from l’Institut français d’Oak Park.