Fathers and Sons

Violetta, the center of the renowned Giuseppe Verdi opera La Traviata, sets the stage for the story during Act I with her aria, “Sempre libera” (“Always Free”). Initially controversial but quickly becoming one of the most frequently performed operas worldwide, La Traviata owes its success to a family whose members, like Violetta, were constantly confronted with challenges from society’s constraints yet claimed the freedom to forge their own paths in life. In the mid-1800s, Verdi was inspired to create La Traviata after attending a theatrical performance of The Lady of the Camellias by Alexandre Dumas fils, the son of writer Alexandre Dumas père, who in turn was the son of military hero Thomas-Alexandre Dumas Davy de la Pailleterie.

Pichat, Olivier. Général Alexandre Dumas (after 1883), Musée Alexandre Dumas, Villers-Cotterëts, France. Image credit: Olivier Pichat, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Thomas-Alexandre was born in Saint-Domingue (now Haiti) in 1762 to Marquis Alexandre Antoine Davy de la Pailleterie, a nobleman from Normandy who became a sugar, coffee, and cacao planter in the Caribbean, and Marie-Cessette Dumas, one of his enslaved workers with whom he had two other children. After the death of the Marquis’ parents and brothers, he returned to France and soon sent for his oldest son while abandoning his two other children and their mother by selling them. Thomas-Alexandre left his home and family at the age of 14 to live with his father in France, where he received an education fitting of a young nobleman that often led to a military profession. However, the norms of the day saw Thomas-Alexandre’s racial background as incompatible with his noble heritage, thus denying him an officer’s commission. Honoring his father’s request that their family name be spared from an association with a lower status, Thomas-Alexandre Dumas enlisted in the French Army as a private two weeks before his father’s passing in 1786.

Dumas served skillfully and honorably, first in France as public unrest built up to and during the Revolutionary years. He was quickly and frequently promoted during subsequent deployments to northern France and Belgium before being given command of the Army of the Western Pyrenees and then the Army of the Alps in 1793. By 1796, Dumas was a general in Napoleon Bonaparte’s forces fighting in Italy and Egypt before being imprisoned in Naples for several years. It is believed that Bonaparte felt overshadowed, literally and figuratively, by the accomplished officer who stood over six feet tall, and capitalized on Dumas’ imprisonment to consolidate his own power to transform the French Republic into an empire. Despite his longstanding loyalty and service to his country, Dumas was repeatedly denied his military pension and died in 1806, leaving his wife and children nearly destitute.

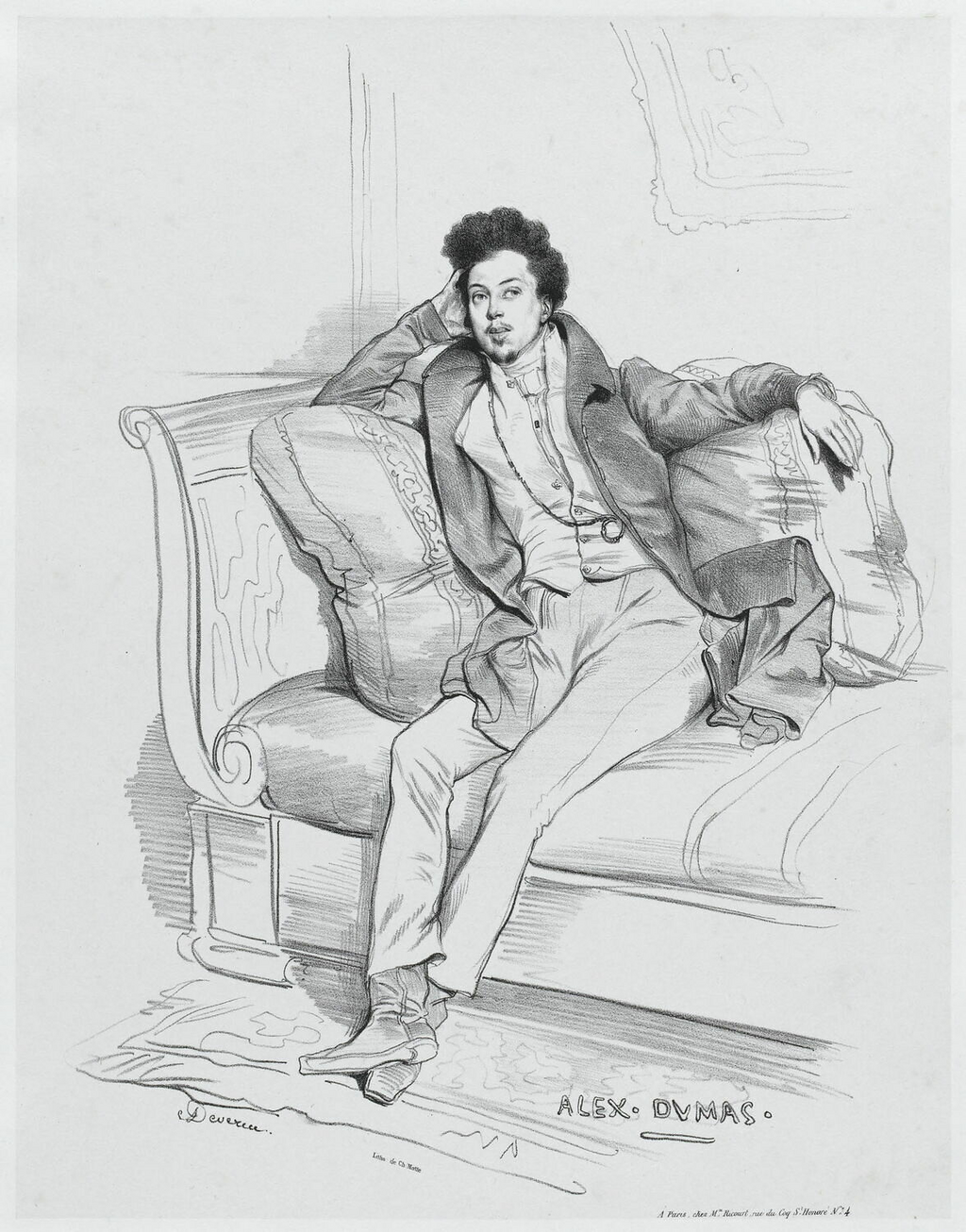

Alexandre Dumas by Achille Devéria (1829). Image credit: Achille Devéria, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Alexandre Dumas lost his father as a toddler but was captivated by stories of his military career and heroism. Raised by his mother, Marie-Louise Labouret, in northern France, Alexandre moved to Paris in 1823 at the age of 21 and found employment as a clerk for Louis-Philippe, Duke of Orléans. He wrote magazine articles and essays on the side as well as receiving an enthusiastic response to his first play, “Henri III et sa cour” (“Henry III and His Court”) when it was first performed in 1829. Continued theatrical successes allowed Dumas to write theatrical works full-time and expand into serial novels published in newspapers. Dumas drew from historical events and his father’s exploits to spin adventure, fantasy, and romantic stories populated with well-known figures from the past. His accomplishments prompted Dumas to establish his own production studio with writing assistants who helped churn out crowd-pleasing tales under Dumas’ direction. His earnings funded travels, life indulgences, and an extensive romantic life as well as the construction of the Château de Monte Cristo outside of Paris, now a museum dedicated to the writer’s life.

Portrait 0f Alexandre Dumas fils. Image credit: See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Of Dumas’ prolific output that grew to include travelogues, a dictionary of cuisine, and libretti for several operas, some of his most lasting works are Les trois mousquetaires (The Three Musketeers) and Le comte de Monte-Cristo (The Count of Monte Cristo), which have been translated into many languages, adapted for the big and small screen, and continue to be enjoyed around the world. With money and success, however, came a seemingly limitless desire for extravagant living and serial philandering that left Dumas barely ahead of his creditors and with tenuous or nonexistent relationships with his four children by different women. His eldest, also named Alexandre Dumas, was born in 1824 to Marie-Laure-Catherine Labay, a dressmaker who raised her son without support during his first seven years until Dumas père acknowledged his paternity. Although the father bestowed an education on his namesake, Dumas fils was profoundly marked by the shame of his illegitimacy and the deplorable treatment of his mother.

Like his father, Dumas fils began writing as a young man and found near-immediate success in 1848 with his novel La dame aux camellias, which he adapted four years later into the play that would lead to Verdi’s La Traviata. And also like his father, Dumas fils was inspired by his father’s deeds but not to glorify them, believing that literature was a means to examine ethical and moral issues. His books and plays generally offered social commentary with an emphasis on the morals and honor that he found wanting in his father’s lifestyle. Dumas felt strongly that men who fathered illegitimate children had a clear obligation to follow through with marriage and paternal care, a direct rebuke to the childhood he had lived and its associated difficulties and emotions. His themes often challenged societal norms of the day with thorny human relationships set among moral quandaries, reflections of realities that Dumas had lived and witnessed in his own life. The works of Dumas fils were critically and commercially admired which resulted in personal wealth and national honors that included induction into the Académie française and being named to the French Legion of Honor. Despite the tone and messaging of the younger Dumas’ published works, he and his father gradually developed a warm relationship.

The generations of Dumas men certainly were born into challenging circumstances and grew up in times when French society was far more rigid than today. Not only did they persevere in their own ways, each also played a significant role, albeit unknowingly and unintentionally, in his son’s eventual path through life and livelihood. The dedication of Thomas-Alexandre in service of his adopted home, the persistent joy of Alexandre (père) to entertaining his readers alongside him, and the literary directive of Alexandre (fils) to reflect on society’s treatment of people who were considered to be lesser yet with lives and feelings demonstrate a thread of seizing the opportunity to be “Always Free” in shaping their own lives and leaving legacies that continue to resonate worldwide.

Jeu de français

Millions of people have become familiar with several of the characters and stories created by Alexandre Dumas père and fils through books, films, opera, and other adaptations. Test your knowledge of the novels of Dumas père by answering ten multiple choice questions in the English-language quiz below.

Subscribe to our newsletter to receive Art de vivre posts, information about courses, Conversation Café, special events, and other news from l’Institut français d’Oak Park.